Introduction & Background

Women’s mobility in India is fraught with social, cultural, and infrastructural limitations, despite the nation’s ongoing progress in education, employment, and economic participation for women. For over 600 million Indian women, the option to travel independently—whether for education, work, healthcare, or community engagement—remains heavily influenced by prevailing gender norms, safety concerns, and a lack of skills training programs aimed specifically at women. This constraint is not simply a transportation issue; it represents a fundamental barrier to gender equality, well-being, and economic empowerment.

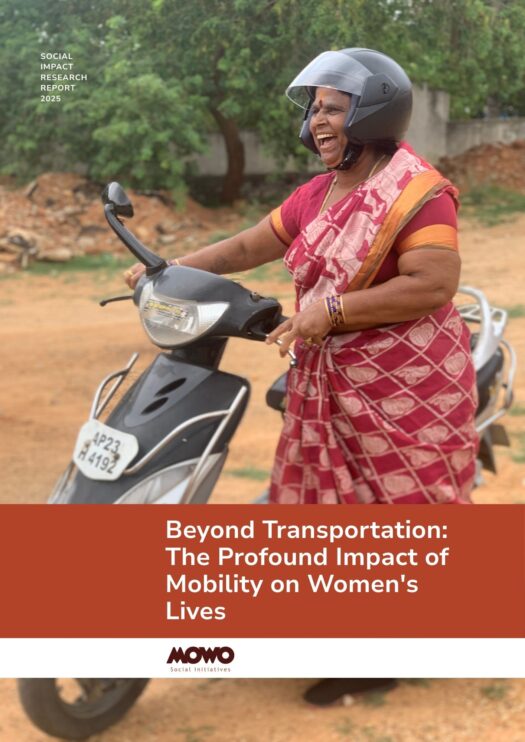

“Beyond Transportation: The Profound Impact of Mobility on Women’s Lives” addresses the question: What happens when women are given the opportunity to acquire motor vehicle operation skills in a supportive, gender-sensitive environment? It investigates how targeted training can catalyze far-reaching changes in individual independence, psychological well-being, social relationships, economic status, and policy discourse.

MOWO Social Initiatives Foundation, Hyderabad, has emerged as a pioneering force in this arena since its founding in 2019. With a mission to enable a million women in mobility by 2030, MOWO’s multi-pronged approach encompasses advocacy, two- and three-wheeler driving training, and the creation of sustainable employment pathways. The study uses MOWO’s impactful programs as a lens to explore the far-reaching consequences—personal, family, community, and policy—of investing in women’s mobility.

Study Objectives

The primary objectives of the research are:

- To measure the social, psychological, and economic impacts of motor vehicle training on women from diverse backgrounds.

- To understand how mobility training correlates with improvements in subjective well-being.

- To identify key enabling and inhibiting factors in implementing such programs at scale.

- To document lived experiences as case evidence for advocacy and policy recommendations.

- To establish baseline data and indicators relevant to measuring well-being in future studies and impact assessments.

Methodology

Design:

The study employs a mixed-methods approach, with qualitative and quantitative data used synergistically to capture both depth and breadth of impact.

- Focus Group Discussions (FGDs):

Four FGDs were conducted between October and December 2024 in Telangana, covering urban, peri-urban, and rural contexts (Narayanpet, Kukatpally trainees, Kukatpally trainers, and BITS Pilani campus staff). Participants represented a diverse cohort: housewives, working women, contract staff, self-help group members, and women with varying levels of formal education. The FGDs deeply explored motivations, experiences, perceived outcomes, and challenges faced during and after training. - WhatsApp Survey:

In March 2025, a quantitative survey (based on Ryff’s Six-Factor Model of Psychological Well-Being) was distributed via WhatsApp to 39 batches of former trainees. The survey was administered in Telugu, Hindi, and English, designed for brevity and mobile friendliness to maximize participation from time-constrained homemakers and working women. - Literature Review:

Findings were contextualized with current literature on mobility, well-being, and gender equity, referencing established frameworks such as the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA), the Capability Approach, and studies on mobility as a form of social and economic capital.

Key Findings

- Psychological Impact and Well-being

Participants consistently reported heightened confidence, autonomy, and a sense of accomplishment following training. Many described the act of learning to drive as a direct parallel to “driving their lives forward,” overcoming deep-seated fears and social stigmas. Training contributed to improved self-acceptance, environmental mastery, and purpose in life—all key pillars of well-being. - Social Capital and Peer Support

Women-only training spaces, and the presence of female trainers (“Madam Trainers”), were instrumental in creating a culturally appropriate, safe, and supportive learning environment. Ongoing WhatsApp peer groups facilitated knowledge sharing, encouragement, and the emergence of long-lasting friendships. Family and community perceptions evolved positively, with women reporting increased respect, reduced dependency, and new opportunities for leadership. - Economic Empowerment

Training increased women’s access to jobs in transportation, delivery services, and allied sectors. Over 300 women have found mobility-based employment via MOWO, while many others cite enhanced ability to manage work, household errands, and family commitments. For rural SHG (Self Help Group) members, access to driving skills correlated with increased political participation and financial independence. - Ecosystem Approach and Institutional Partnerships

MOWO’s ecosystem strategy—linking trainers, learning infrastructure, and community peer groups—proved highly effective in reducing attrition, building confidence, and increasing skill transfer rates. Partnerships with government bodies (e.g., Department of Women & Child Welfare, Telangana State Women’s Cooperative Development Cooperation, BITS Pilani, PURE EV) facilitated scale, technical credibility, and financial support for driver licensing. - Advocacy and Scaling

National advocacy campaigns (“Moving Boundaries”), targeting both internal and external stakeholders, have reached over 25,000 women to date, breaking stereotypes and generating vital public discourse on gender and mobility. MOWO has demonstrated the feasibility of scaling such programs through institutional buy-in and policy-level support. - Barriers and Challenges

Despite successes, challenges remain: ongoing safety and infrastructure issues, societal gender norms, and variable access to affordable vehicles. Some women, while trained, still preferred public transport due to external risks or a lack of experience navigating unfamiliar routes. These insights underscore the need for complementary interventions in public safety, urban design, and mindset change.

Data Analysis Framework

The study organizes qualitative findings via four capital types (derived from SLA):

- Psychological Capital: Hope, resilience, optimism (confidence, reduced fear).

- Human Capital: Knowledge, technical and navigation skills, license acquisition.

- Social Capital: Peer relationships, group membership, familial support.

- Economic Capital: Direct job placement, increased household income, better work-life balance.

Survey data highlighted strong correlations between participation in MOWO programs and increases across all six Ryff dimensions of well-being: self-acceptance, positive relations, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth.

Case Examples

- Narayanpet: Rural SHG participants noted improvement in community recognition and inclusion, with training acting as a catalyst for further participation in political and social spheres.

- Kukatpally: Urban participants (trainees and trainers) highlighted new career pathways (e.g., becoming instructors), and increased family support.

- BITS Pilani collaboration: Around 200 contract women workers gained access to e-mobility training, with the campus subsidizing license fees, resulting in greater workplace inclusion and mobility.

Policy Implications & Recommendations

The research recommends the following to maximize impact:

- Expand Advocacy and Awareness Campaigns: To reach marginalized women across geographies and income segments.

- Launch Gender-Sensitive Road Safety Initiatives: Integrate women’s perspectives and needs into road safety and public transit policies.

- Establish and Scale Women-led Training Centers: Leverage government subsidies, policy support, and public-private partnerships.

- Promote and Upskill Female Trainers: To serve as mentors and scalable models of real-world change.

- Ongoing Research and Data Collection: For continuous improvement, policy validation, and evidence-based advocacy.

Alignment with UN SDGs

MOWO’s work is directly aligned with six Sustainable Development Goals: Gender Equality, Quality Education, Decent Work & Economic Growth, Sustainable Cities & Communities, Good Health & Well-Being, and Climate Action. By empowering women with progressive skills (including EV operation), the project advances both gender and sustainability agendas.

Conclusion

Women’s independent mobility, long constrained by gender and cultural norms, is emerging as a powerful lever for social transformation in India. The MOWO model demonstrates that targeted, ecosystem-based training programs can produce compounding benefits: boosting self-esteem, fostering peer networks, unlocking economic opportunities, and shifting community perceptions of gender roles.

Empowering women to drive is not merely about movement—it enables access to a fuller spectrum of choices, freedoms, and resources. As India moves toward its 2030 goals, such integrated approaches offer scalable blueprints for inclusive policy, industry partnerships, and research collaborations. MOWO’s ambition—to enable a million women’s mobility journeys by 2030—stands as a clarion call for gender equity, development, and sustainable progress.